Knee Problems

- Acromioclavicular Joint Dislocation

- Achilles Tendon Injuries

- Ankle Problems

- Cruciate Ligament Injury

- Orthopedic Problems of Dancers

- Knee Problems

- Ganglion Cyst

- Hallux Rigidus

- Hallux Valgus

- Carpometacarpal Joint Arthritis

- Meniscus Tear

- Orthopedic Problems of Musicians

- Olecranon Fracture

- Shoulder Dislocation

- Shoulder Problems

- Osteoartrit

Contact Us

You can contact us to answer your questions and find solutions for your needs.

M. Tibet Altuğ M.D. Contact

M. Tibet Altuğ M.D.

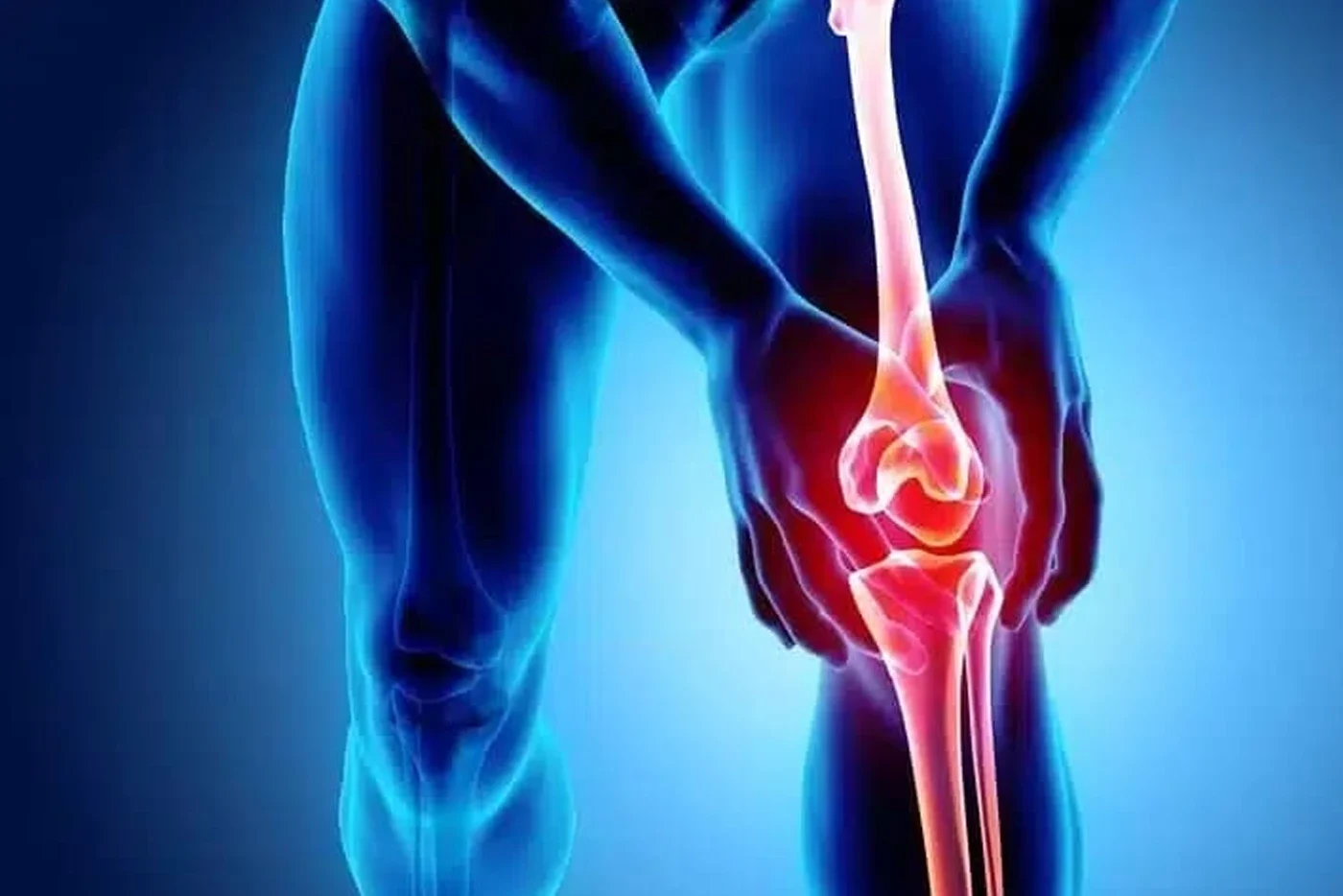

Knee Problems

In the knee joint, a wide variety of issues can occur over the long span from birth to old age, including meniscal injuries, anterior-posterior and collateral cruciate ligament injuries, cartilage and joint problems, as well as osteoarthritis.

In the knee joint, a wide variety of issues can occur over the long span from birth to old age, including meniscal injuries, anterior-posterior and collateral cruciate ligament injuries, cartilage and joint problems, as well as osteoarthritis.

Meniscus Problems

The menisci are crescent-shaped, elastic cartilaginous structures located on the load-bearing surface of the knee joint. They function like shock absorbers while also enlarging the weight-bearing surface of the joint, increasing the congruity between joint surfaces, preventing abnormal joint motion, and helping joint fluid coat the cartilage surface.

When the leg is straight, the menisci carry about 50% of the body weight. When the knee is flexed at 90 degrees, this load increases to 90%. The lateral meniscus is biomechanically more significant than the medial meniscus.

Meniscal injuries are among the most common orthopedic injuries. The location, type, and size of the tear in the meniscus are important in determining the treatment plan. Both non-surgical and surgical treatment methods are applied.

Non-surgical methods:

Not all meniscus tears require surgical treatment (such as “stable” tears that do not cause symptoms like catching or locking, short tears, and degenerative tears commonly seen in arthritic knees). In these cases, treatment focuses on alleviating the patient’s symptoms. Common methods include ice application, anti-inflammatory medications, and physical therapy aimed at regaining joint range of motion and strengthening surrounding muscles. Additional treatments may include high-intensity laser therapy (HILT), manual therapy, matrix rhythm therapy, kinesiotaping, and dry needling.

Surgical treatment methods:

Meniscectomy: Partial or total removal of the meniscus. The less meniscal tissue removed, the better the long-term outcomes. Only the mechanically problematic (catching, locking) portion is removed. This surgery, performed arthroscopically (minimally invasive), allows patients to return to daily life shortly after.

Meniscus repair: Considering the functions of the menisci, the importance of repair becomes evident. Not all tears are suitable for repair, but repair should be performed whenever possible. In knees without ligament issues, success rates for repair—regardless of technique—are reported to range from 70% to 95% in various studies.

Meniscus transplantation: Practiced for over fifteen years. It is used in patients with persistent complaints following partial or total meniscectomy. However, the candidate should not have lower extremity alignment problems, ligament injuries, or serious cartilage damage.

Knee Ligament Injuries

a) Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)

ACL injuries most frequently occur during sports activities. About 70% of individuals with an ACL injury report a twisting motion in the knee. Swelling occurs within the first 24–48 hours after injury. In the long term, the most common complaint is a feeling of instability. ACL injuries can occur in isolation or along with meniscus, cartilage, or other ligament injuries. Therefore, careful physical examination and appropriate radiological evaluations are important.

Cerrahi olmayan tedavi: Partial tears and low-energy ski injuries are suitable candidates for non-surgical treatment. This includes strengthening surrounding muscles and proprioceptive (positional sense) exercises. Rehabilitation training programs, HILT, and matrix rhythm therapy may also be beneficial. Adjusting physical activity (such as avoiding contact sports) is also advised.

Surgical treatment:

Athletes involved in sports like football, basketball, handball, and tennis generally cannot return to sport without surgery. Even amateur athletes are recommended surgery to prevent additional injuries (e.g., cartilage, meniscus).

Additionally, ACL reconstruction should be considered for individuals with physically demanding jobs (e.g., soldiers, police officers, firefighters). However, not all athletes necessarily require ACL reconstruction. For example, amateur skiers not participating in competitions have been shown to continue skiing without surgery.

People who are not involved in sports or are older can often live their lives without ACL reconstruction. However, if these individuals experience instability, surgery may be necessary.

Grafts used in surgery can be autografts (from the patient) or allografts (from a donor). Full range of motion and strong surrounding muscles prior to surgery are important for successful outcomes. Return to sports ranges from 6 to 12 months depending on rehabilitation progress.

b) Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)

The PCL is thicker than the ACL and is less likely to cause instability when injured alone. As a result, PCL injuries may be overlooked and lead to slow, insidious osteoarthritis.

PCL injuries may occur alone or with other ligament injuries. If three or more ligaments are injured, it is considered a knee dislocation. PCL injuries (especially those with multiple ligament involvement) can lead to joint instability, pain, and long-term osteoarthritis.

PCL injuries may involve partial tears, complete tears, or multiple ligament injuries.

Non-surgical treatment:

Used in isolated PCL injuries or patients unable to undergo surgery with multiple ligament injuries. Treatment includes strengthening muscles around the knee and proprioceptive exercises. Rehabilitation training, HILT, and matrix rhythm therapy may help. Adjusting physical activities (e.g., avoiding contact sports) is also beneficial.

Surgical treatment:

Various techniques and graft options, as in ACL injuries, are available.

c) Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) and Posteromedial Corner (PMC) Injuries

The MCL is the most commonly injured ligament in the knee. The most frequently injured ligament alongside the MCL is the ACL. About 5% of MCL injuries are accompanied by medial meniscus injuries. Static and dynamic supports on the medial side of the knee exist in three layers. The MCL is the most important of these. It primarily prevents valgus (inward) movement of the knee. Other support tissues (PMC) also help prevent valgus and external rotation.

There are three grades of MCL injury:

Grade I: Few fibers are damaged. The ligament remains intact.

Grade II: Partial tear. The ligament can still function.

Grade III: Complete rupture.

Non-surgical treatment:

Suitable for Grade I and II MCL injuries, as well as Grade III injuries without cruciate ligament involvement or valgus laxity in extension. Crutches and bracing may be used in severe cases. Physical therapy, muscle strengthening, and proprioceptive exercises are key. Rehabilitation programs, HILT, and matrix rhythm therapy are also helpful. Modifying sports participation is beneficial.

Surgical treatment:

Recommended if instability persists despite bracing and physical therapy, valgus laxity in extension is present, or if cruciate ligament injuries are also present.

d) Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) and Posterolateral Corner (PLC) Injuries

Reported to occur in 7–16% of all knee injuries. The lateral side of the knee has both static and dynamic stabilizers, like the medial side. The LCL primarily prevents varus (outward) movement. Most LCL and PLC injuries result from sports trauma or motor vehicle accidents. They are often accompanied by cruciate ligament injuries. Patients may have difficulty going up/down stairs or turning and experience pain along the lateral joint line. Isolated LCL injuries are rare; they usually involve rotational instability with cruciate or PLC injuries.

PLC injuries are graded by comparing to the opposite knee:

Grade I: 0–5 mm joint opening

Grade II: 6–10 mm joint opening

Grade III: More than 10 mm opening

Non-surgical treatment:

Limited to isolated Grade I and II LCL injuries without damage to other structures. Return to sports is possible within 6–8 weeks. Includes muscle strengthening, proprioceptive training, rehabilitation programs, HILT, and matrix rhythm therapy. Avoiding contact sports is advised.

Surgical treatment:

Recommended for complete LCL tears, combined PLC injuries, and LCL/PLC injuries with cruciate ligament involvement. Early surgery (within two weeks of injury) yields better results than delayed repair.

e) Multiple Ligament Injuries

Usually result from high-energy trauma and are also referred to as knee dislocations. Rarely, they may occur in obese individuals during daily activities. Risk of vascular compromise is present. In cases with additional health risks, advanced age, patient refusal, or partial ligament injuries, conservative treatment may be considered. Outside of these, surgical treatment is standard for multiple ligament injuries.

Cartilage Problems in Knee Area

Traumatic cartilage problems typically result from blunt trauma to the knee or abnormal motion causing ligament damage. Joint swelling and pain during weight-bearing are common. Cartilage damage is classified based on area, depth, and shape.

Treatment options are evaluated according to classification. Both surgical and non-surgical methods are available.

Non-surgical treatment:

Recommended for cartilage damage with bone marrow edema but no cartilage surface disruption. Includes using crutches for non-weight-bearing walking, rest, and ice until swelling and pain subside. Co-existing injuries should be addressed. Return to pre-injury activity typically takes around three months. The joint cartilage has self-repair capability under appropriate physiological stimuli. Exercise programs should be tailored to the patient’s age, weight, and activity level.

Surgical treatment:

Indicated when symptoms persist despite conservative treatment, cartilage surface depression exceeds 2 mm in weight-bearing areas, there’s osteochondral separation or fracture, or subchondral bone is exposed. Surgical techniques include fixation of osteochondral fragments, abrasion, subchondral drilling, microfracture to stimulate new cartilage growth, and osteochondral autograft transfer (mosaicplasty).

4. Patellofemoral Joint Problems

Anterior knee pain (AKP, patellofemoral pain) is the most common knee complaint in adults and adolescents. About one-third of knee pain originates from the patellofemoral joint. AKP has multiple causes, categorized as biological, mechanical, or psychological.

AKP may develop acutely or chronically. Common causes include tenosynovitis, cartilage damage, patellofemoral misalignment, and synovial impingement syndrome. In chronic cases, psychological status should also be considered.

Non-surgical treatment:

Most AKP cases can be managed non-surgically. Exercise types should be chosen according to the tissue involved and the healing stage. Physical therapy should differ based on whether the pain stems from cartilage, tendon, bone, or muscle. Activity modification and physical therapy (taping, pain-limited strengthening, orthotic use) help reduce patellofemoral load.

Surgical treatment:

Surgery is indicated for pain due to patellar instability. Inflammatory peripatellar tissues (e.g., plica syndrome, synovial impingement, fat pad syndrome) may also be surgically treated.

Patellar Dislocation:

Occurs when the patellofemoral alignment is partially or completely disrupted. Causes include bone structure and soft tissue abnormalities. The medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) prevents lateral displacement of the patella and tears during dislocation.

Surgery is not performed after the first dislocation unless there are loose cartilage fragments in the joint requiring arthroscopic debridement or fixation. MPFL reconstruction is used for acute or recurrent dislocations. Treating underlying causes is essential in recurrent cases.

5. Knee Osteoarthritis (OA)

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative joint disease caused by cartilage loss. It is most commonly seen in the knee. Many cases have no clear cause, but risk factors include age, weight, family history, sex, and ethnicity. Known (secondary) OA can have various causes. Symptoms include joint stiffness, cracking sounds during movement, tenderness, swelling, and deformity depending on disease severity.

Over time, walking distance decreases, and patients struggle with stairs or squatting. Treatment is planned based on disease stage:

Non-surgical treatment:

Includes activity modification, pain relievers, joint injections, orthoses, assistive devices, and physical therapy. Modern physical therapy involves more than heat/cold applications and electrotherapy. Methods like kinesiotaping, high-intensity laser therapy, manual therapy, and dry needling are also used. While applying non-surgical methods, factors like pain threshold, edema, active range of motion, and daily activity levels must be considered.

Surgical treatment:

Considering the stage of the disease and surgical requirements; arthrodesis, high tibial osteotomy, unicondylar or total knee arthroplasty may be applied.